Via Andrew Sullivan we have this piece by William B. Hurlbut, Consulting Professor in the Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University Medical Center, a man of science, who is, it turns out, also a fan of the benevolently deranged Francis of Assisi.

Via Andrew Sullivan we have this piece by William B. Hurlbut, Consulting Professor in the Department of Neurobiology, Stanford University Medical Center, a man of science, who is, it turns out, also a fan of the benevolently deranged Francis of Assisi.

There’s plenty in the article for those with an interest in Francis himself, but I was more interested in this:

The traditional role of medicine, for example, has been to cure disease and alleviate suffering, to restore and sustain the patient to a natural level of functioning and wellbeing. The medical arts were in the service of a wider reverence and respect for the order of the created world: “the physician is only nature’s assistant,” as the Roman healer Galen explained.

But now, armed with the powers of biotechnology, medicine has found a new paradigm, one of liberation: technological transformation in the quest for happiness and human perfection. Slowly but steadily the role of medicine has been extended, driven by our appetites and ambitions, to encompass dimensions of life not previously considered matters of health, with the effect of altering and revising the very frame of nature. Increasingly, we expect from medicine not just freedom from disease but freedom from all that is unattractive, imperfect, or just inconvenient. More recent proposals, of a still more ambitious scope, include projects for the conquest of aging, neurological fusion of humans and machines, and fundamental genetic revision and guided evolution — for transhumans, posthumans, and technosapiens.

The danger is immediately evident…

It is? Danger? This all sounds splendid, although count me skeptical as to how far we will get any time soon towards, uh, transhumans, posthumans, and technosapiens. I’m still waiting for flying cars and Moonbase Alpha (which was due sometime before 1999).

Hurlbut continues:

In the absence of any concept of cosmic order, where the material and the moral flow forth from a single creative source, all of living nature becomes mere matter and information to be reshuffled and reassigned for projects of the human will.

Well, that absence is what it is. Hurlbut may be uncomfortable with the consequences, but they are what they are—and they need to be faced. He may wish to believe in a “cosmic order” (a fantasy that takes many forms, in any event), but he ought not to be surprised that there are those that disagree that such a thing exists and are thus reluctant to comply with its supposed rules. But that is not necessarily cause for despair. Experience shows that humility and caution in matters of this type are a matter of commonsense, and commonsense has a way, quite often, of winning out. As, if less frequently, does kindness:

Genetically engineered featherless chickens for cheaper pot pies and leaner pigs with severe arthritis are a violation of basic kindness and courtesy.

Well yes.

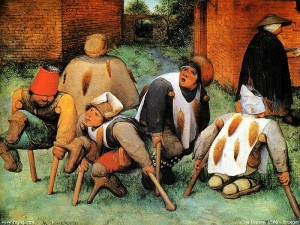

There’s a great deal more from Hurlbut, and, much of it like the writings of Leon Kass, is, in its glorification or, at least, inshallah acceptance of suffering, as morbid, and, in its implications, as revolting as some of the more lurid iconography of Christian martyrdom. It’s sad to see such words flowing from the pen or keyboard of a doctor who will in his own career surely have done a great deal to alleviate the suffering of others. Such are the contradictions of religious faith.

And then there’s this:

[O]ne can sense a wisdom in the severity and self-denial that were, for Francis, inseparable from the source of his joy. He had rediscovered an ancient truth in the inversion of desire, not as a negation of being but as a positive passion. In the image of the Lord, he emptied himself and received all things back renewed, purified, and restored in their divine glory.

When I read that, I see only an expression of a millennial asceticism that in our modern era has found expression not in the kindly ramblings of an oddball hippy saint, but in revolution, gulag, and the emptied streets of Phnom Penh.

Compared with that, biotechnological advance is relatively risk-free…