Here’s Melvyn Bragg writing in the Daily Telegraph on the topic of William Tyndale (and Thomas More):

After almost 500 years, Tyndale continues to command our language and when we reach for the clinching phrase, we still reach out for him.

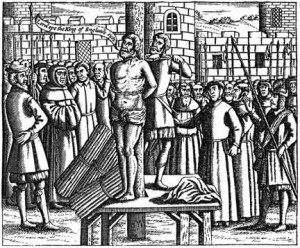

Tyndale was burned alive in a small town in Belgium in 1536. His crime was to have translated the Bible into English. He was effectively martyred after fighting against cruel and eventually overwhelming forces, which tried for more than a dozen years to prevent him from putting the Word of God into his native language. He succeeded but he was murdered before he could complete his self-set task of translating the whole of the Old Testament as he had translated the whole of the New Testament.

More than any other man he laid the foundation of our modern language which became by degrees a world language. “He was very frugal and spare of body”, according to a messenger of Thomas Cromwell, but with an unbreakable will. Tyndale, one of the greatest scholars of his age, had a gift for mastering languages, ancient and modern, and a genius for translation. His legacy matches that other pillar of our language – Shakespeare, whose genius was in imagination….

[Tyndale’s] story embraces an alliance with Anne Boleyn, an argument covering three quarters of a million words with Thomas More, who was so vile and excrementally vivid that it is difficult to read him even today. Tyndale was widely regarded as a man of great piety and equal courage and above all dedicated to, even obsessed with, the idea that the Bible, which for more than 1,000 years had reigned in Latin, should be accessible to the eyes and ears of his fellow countrymen in their own tongue. English was his holy grail….

And, almost as an accidental by-product, he loaded our speech with more everyday phrases than any other writer before or since. We still use them, or varieties of them, every day, 500 years on. …

As a young man he was told by a cleric that it would be better “to be without God’s laws than the Pope’s”.

Tyndale, outraged, replied that he defied the Pope and all his laws and added “If God spares me… I will cause the boy that driveth the plough to know more of the Bible than thou doest”.

The image of the ploughboy was brilliant – because the ploughboy was illiterate. Tyndale deliberately set out to write a Bible which would be accessible to everyone. To make this completely clear, he used monosyllables, frequently, and in such a dynamic way that they became the drumbeat of English prose. “The Word was with God and the Word was God”….

And when his English-language New Testament came out….

The Bishop of London bought up an entire edition of 6,000 copies and burned them on the steps of the old St Paul’s Cathedral. More went after Tyndale’s old friends and tortured them. Richard Byfield, a monk accused of reading Tyndale, was one who died a graphically horrible death as described in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. More stamped on his ashes and cursed him. And among others there was John Firth, a friend of Tyndale, who was burned so slowly that he was more roasted.

Fast forward half a millennium to a report in the New York Times lat year:

Cardinal Timothy M. Dolan on Friday helped kick off a national campaign opposing President Obama’s health care mandates and other government policies that Roman Catholic leaders say threaten their religious freedom…. The bishops timed the two-week campaign of prayer, fasting and letter-writing to begin on a feast day commemorating two 16th-century Catholic saints executed for their religious beliefs — SS. John Fisher and Thomas More. The campaign will conclude on the Fourth of July.

The problem, however (as I discussed here last August) is that More died not in the name of “religious freedom”, but in defense of the supremacy of his religious faith over those of others.

We should be careful before we judge a man of the sixteenth century by the standards of the twenty-first (or even the twentieth). More was no Dzerzhinsky, but he was a clear step down the road that led to men like that.

That ought to be food for more thought than is currently the case.

“We should be careful before we judge a man of the sixteenth century by the standards of the twenty-first (or even the twentieth). More was no Dzerzhinsky, but he was a clear step down the road that led to men like that.”

I’m more comfortable with the first sentence here than with the second.

Which is not to say that there are no parallels between the Catholic Church as it once was and Marxist-Leninist tyranny.

Also, it appears that Bragg, in his journalistic enthusiasm, got Tyndale’s mode of death wrong. Burned, yes – but not burned alive. Strangled first. Small mercies.

Actually Bragg did mention the strangulation. It was reported, however, that this was not fully effective, and Tyndale recovered consciousness in the flames, somehow remaining stoic.

On the evidence of his life, a thoroughly admirable man, for his intellectual abilities, courage, and integrity. Unlike More, however, he never had the temptation of being in the position to enforce his opinions. If he had, one would like to think that he would have been more tolerant of those who disagreed with him, but we’ll never know.

Bragg’s full account, which I have just read, has got my contrarian instincts twitching again. It reads like a hagiography. But, even so, some of Tyndale’s personality traits seem unattractive.

“We read in contemporary sources that as a young man, a tutor and chaplain back in the Cotswolds after university, in a rich household that hosted dinners for local abbots and archdeacons, he became notorious for proving the arguments they put forward to be wrong.”

A bit of a smart arse? Can one also detect a streak of sanctimonious arrogance?

“Anne Boleyn took Tyndale’s side and for a time it seemed that she had reconciled Henry and the scholar whose support of his claim for a divorce he so longed for. But Tyndale’s deeper studies convinced him that the King had no case in Divine Law…”

And I am just a little bit skeptical of the botched-strangulation story. I don’t know how a recently killed body would respond to the flames. It might move in such a way as to appear to wake up. Note that he didn’t speak or cry out. According to Bragg, “… the first flames brought Tyndale back to consciousness. It is reported that he endured the flames in silence.” (As he certainly would have were he already dead.)

Mark, some possibly, but compared with A Man For All Seasons…