Ayaan Hirsi Ali has been calling for an Islamic ‘reformation’. Dan Hannan is not so sure that that’s right:

Ayaan Hirsi Ali has been calling for an Islamic ‘reformation’. Dan Hannan is not so sure that that’s right:

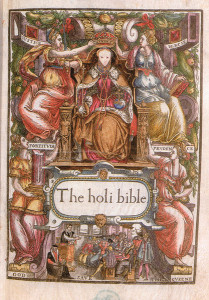

What, though, do we mean by “Reformation”? Most people mean that they want a more modern Islam, one which accepts the separation of church and state, the equality of women, the supremacy of Parliament and so on. This, though, is very far from what the Christian Reformation was about. Its architects were not seeking a cuddlier, more ecumenical version of their faith. On the contrary, just like today’s Salafists, they wanted to purge and purify, to go back to an older and more demanding template, one more closely tied to the Scriptures….

Instead of a Reformation, we might do better speak of an Enlightenment. The reconciliation of Christianity with secularism and pluralism owes less to Luther and Calvin than to Milton and Locke. The West, over the centuries, became less cruel, more intolerant of torture and violence, readier to see other points of view, keener on individual rights and on democracy – and, as it did so, certain religious strictures dating from the Iron Age fell naturally into desuetude.

The abolition of slavery, for example, was a process largely driven by evangelical Christians. Not because they had suddenly discovered Biblical verses condemning servitude – there are none – but because their understanding of their faith had adapted as their world became kinder. Likewise, the reintroduction of slavery in ISIS-held territory revolts most Muslims, not because of any Koranic injunctions – again, there are none – but because the institution belongs to an older, uglier epoch. We have, as the saying goes, moved on.

Dan is right, but there is something else. The Reformation was a rejection of a united Christendom—a Christian ‘ummah’, if you like, an idea already badly damaged by the split with Eastern Orthodoxy— and, in essence, its replacement with something more secular, a series of national (protestant) churches subordinated to local secular authority rather than universalist Rome. As such it was both an intellectual and a political process.

As I posted here, England’s Henry VIII went to his deathbed considering himself a good Catholic. His dispute with Rome was not over theology, but power. Henry wanted more of the latter (and Anne Boleyn too) but the underlying (and ultimately more important) question was whether England should be governed by English laws or those of some alien authority. Henry VIII, quite correctly, if for self-interested reasons, said that the law begins at home. Within a few decades the Church of England had set off on its own.

Meanwhile, the Peace of Augsburg (1555) had accepted the principle that within the Holy Roman Empire, the rule that would apply would be cuius regio, eius religio. As the local prince worshiped (the choice was between Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism) , so would his people.

And it’s hard not to think that Christianity’s intellectual authority of was not dented by this development. The notion of a universal overarching truth had been trashed and what’s more, particularly in northern Europe, God had, in a sense, been reduced to a rank below Caesar, a demotion that must, I suspect, played its part in clearing the way for the Enlightenment.

The way I’ve always heard this explained is that Islam has had no Reformation because Islam has had

no Pope. It’s -already- a very diffuse, many-headed faith.

I love AHA, and wish I could see her and her buds while they convene in my city this weekend, but that would cost money (unless CSpan is there, and I think they’ve covered the Atheists’ meet-ups in years past).

Narr