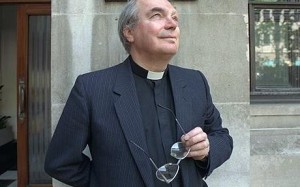

Writing in The Daily Telegraph, Peter Mullen, a British parson, attempts to clothe his religiously-based objections to assisted suicide (“As a Christian, I do not believe we have the right to die at the moment and by the means of our own choosing. Suicide is a mortal sin.”) in what he pretends are “utilitarian” arguments:

Writing in The Daily Telegraph, Peter Mullen, a British parson, attempts to clothe his religiously-based objections to assisted suicide (“As a Christian, I do not believe we have the right to die at the moment and by the means of our own choosing. Suicide is a mortal sin.”) in what he pretends are “utilitarian” arguments:

First to be considered is the effect on the morals, the conscience and the psychology of the doctor who has allowed himself to conspire in the killing [suicide] of another human being.

Well, that rather presumes that the doctor believes that there is something wrong with acceding to his patient’s request, something that is unlikely given the right that would undoubtedly be given to doctors opposed to assisted suicide to hand this task over to someone else.

I note too that Mullen has nothing to say about “the effect on the morals, the conscience and the psychology of the doctor” who has allowed himself to conspire in the prolongation of the agony of a patient looking for release.

His argument limps on:

Every case of assisted killing [suicide] will be different from every other case. How, for example, in the case of a very sick person, do we assess the balance of his mind: is he capable of being certain that he wishes to end it? And who is to vouch for that certainty?

Who is this, “we”, Vicar? If the patient is sane, the decision is his. I don’t believe in there being a right to assisted suicide, or many other non-legislated rights for that matter, but I do think that a civilized society ought not to stand in the way of a patient to ask for the help he needs to bring his suffering to an end.

Then there’s this:

And it could even be that someone one day expresses the wish to die but that, days or weeks later, he changes his mind. Of course, if he is dead that possibility is no longer open to him.

Oh please. Most of those who support changes to the law also support waiting periods and other safeguards. That said, a society that attributes real value to individual self-determination will also recognize that individuals make mistakes and that sometimes those mistakes are irrevocable. That goes with the territory.

And, of course, there’s this old chestnut:

And then it is well-known that human beings are not perfect. Might some relatives of a very sick man try to persuade him to do away with himself – perhaps even to inherit his money?

Yes, that would be wicked, but how much more wicked is it really than denying a patient the right to end his agony in the name of a religious belief that he does not share?

Mullen, I’d hope, is not a cruel man, but the consequences of his absolute certainty can, at their worse, be monstrous. He should have the humility to remember the wisdom of Oliver Cromwell’s great request:

I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.