One thing about this pope: When it comes to political matters, he has an unerring ability to be on the wrong side of the issue.

Pope Francis on Friday received the International Charlemagne Prize of Aachen, Germany, from Marcel Philipp, the Lord Mayor of the German city. The International Charlemagne Prize is awarded for work done in the service of European unification.

The Vatican Radio report includes the full transcript of Francis’ speech.

A couple of extracts caught my eye:

[W]e would do well to turn to the founding fathers of Europe. They were prepared to pursue alternative and innovative paths in a world scarred by war. Not only did they boldly conceive the idea of Europe, but they dared to change radically the models that had led only to violence and destruction. They dared to seek multilateral solutions to increasingly shared problems.

It is certainly true that these founding fathers did conceive an “idea of Europe”, but it was one with little connection to history, and even less to democracy.

As a reminder of that, the Daily Telegraph reports recent comments from Jean-Claude Juncker, the EU’s top bureaucrat, one of the apparatchiks present to watch the Pope receive his prize (my emphasis added):

Prime Ministers must stop listening so much to their voters and instead act as “full time Europeans”, according to Jean-Claude Juncker. Elected leaders are making life “difficult” because they spend too much time thinking about what they can get out of EU and kowtowing to public opinion, rather than working on “historic” projects such as the Euro, he said.

Note that use of “historic”, with its suggestion that there is a “right” side of history, a notion that comes, wrote Robert Conquest, that great historian of Soviet communism, with a “Marxist twang”.

And then there was this from the Pope:

The roots of our peoples, the roots of Europe, were consolidated down the centuries by the constant need to integrate in new syntheses the most varied and discrete cultures. The identity of Europe is, and always has been, a dynamic and multicultural identity.

Clearly, that is an indirect reference to the current immigration wave, a wave that Francis has, in his own way, done his bit to encourage, but it is a view difficult to reconcile with historical reality.

Yes, European peoples have enriched their cultures by learning from others, but they have also defended their distinctiveness of their cultures, and, as the years passed and Habsburgs faded, they increasingly did so behind national borders that created a space for a diverse Europe to develop and to flourish, something very different from the multicultural Europe that the Pope appears to be describing. There was pluribus, but not so much unum.

This process gathered pace as those national borders solidified, hugely accelerated by the manner in which ‘Christendom’, the Roman Catholic ummah, already divided by the breach with the East, was further fragmented by the Reformation, a movement that was political as well as religious.

Writing on this topic the (admittedly not uncontroversial) British politician, Enoch Powell, looked at Henry VIII’s break with Rome, arguing in 1972 that:

It was the final decision that no authority, no law, no court outside the realm would be recognized within the realm. When Cardinal Wolsey fell, the last attempt had failed to bring or keep the English nation within the ambit of any external jurisdiction or political power: since then no law has been for England outside England, and no taxation has been levied in England by or for an authority outside England—or not at least until the proposition that Britain should accede to the Common Market [the future EU].

And this is not just an English thing. Writing in the Guardian, Giles Fraser notes that:

Research by social scientist Margarete Scherer from the Goethe University in Frankfurt has demonstrated a considerably higher prevalence of Euroscepticism in traditionally Protestant countries than in traditionally Roman Catholic ones. And this should be entirely unsurprising, given that the Reformation was largely a protest about heteronomous power.

Heteronomous!

Fraser:

As Cardinal Vincent Nichols said last month: “There is a long tradition in … Catholicism of believing in holding things together. So the Catholic stance towards an effort such as the EU is largely supportive.” Of course, the important question is: who does the “holding things together”? And for the cardinal – theologically, at least – it’s Rome.

Conversely, in Protestant countries, the EU still feels a little like some semi-secular echo of the Holy Roman Empire, a bureaucratic monster that, through the imposition of canon law, swallows up difference and seeks after doctrinal uniformity. This was precisely the sort of centralisation that Luther challenged, and resistance to it is deep in the Protestant consciousness…

Writing in Britain’s Catholic Herald, Ed West questions the Pope’s decision to accept the Charlemagne prize:

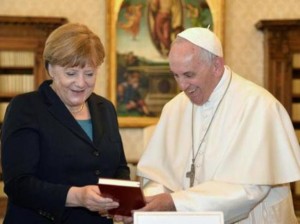

Francis is a great advocate of peace and brotherly love, but it is surprising that he has accepted an award that is so nakedly political, especially as the EU faces next month the first vote by a member state on leaving. It is one thing to promote “European unity” in the abstract, but this award explicitly promotes the cause of the EU, as can be shown by its recent winners, among them Donald Tusk, Herman Van Rompuy, Angela Merkel and, in 2002, “the euro”. Sure, from deep within Charlemagne’s empire the euro might have appeared to have promoted unity, but for Greece’s huge numbers of unemployed youths it probably does not seem that way.

Many, many British Catholics oppose our membership of what strikes us as a hugely risky attempt to create a superstate, despite such ventures normally ending in disaster; we know that the bishops both on the continent and in this country overwhelmingly support this venture, but it seems odd that the Holy Father should so openly take one side in a controversial political matter.

Not so much, I reckon.